Welcome to my series of blog posts Travels in Scotland. Whether you're planning a trip, reliving a memory, or relaxing into some armchair traveling...thank you for joining me! Here I will show you images & share stories of my one month travels through Scotland. I'll cover this beautiful country of mountains, rivers, glens, islands, history, and, of course, fiber and textiles.

The orkney islands

Traveling to the far north of the Scottish Mainland, the Orkneys are an archipelago of 70 islands and rocky reefs. Twenty of the Orkney Islands are inhabited today. The Orkney Islands themselves have been inhabited for 8,500 years. Located at the northern most tip of Scotland, about 235 miles from Norway, the Orkneys along with Shetland, were once part of the Danish and Norwegian kingdoms. There is a shared Norse history, but of course the Orkneys have their own identity. You remember the 2014 Scottish referendum for independence from the UK, but did you know that in 2023, the Orkney Islanders considered becoming a Norwegian territory and in 1967 voted on the question of becoming a Danish territory? These votes are clues to the visitor/outsider that islanders have a unique character and fierce independence.

North Ronaldsay Seaweed-eating sheep

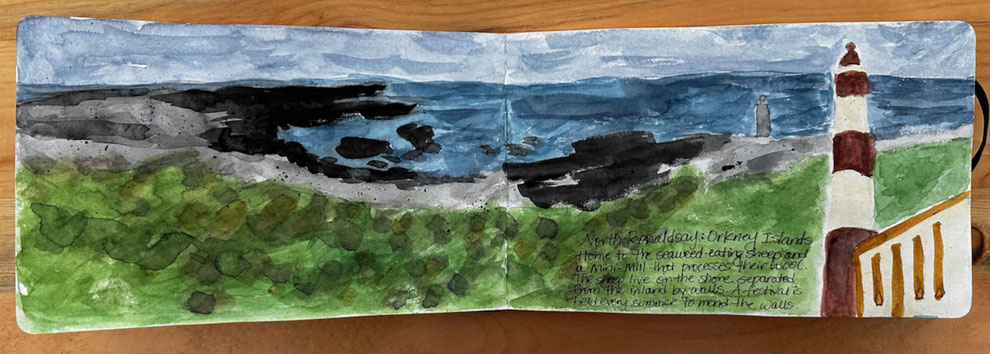

At the furthest north of all the Orkney Islands, lies North Ronaldsay inhabited by 72 people and 2,500 sheep. Traditionally, the islanders of North Ronaldsay exported kelp, but when that industry collapsed in the 1830's, the inhabitants looked for another means to earn money. They built a wall around the island to keep cattle on the grassy interior, and pushed the North Ronaldsay sheep onto the seashore. The sheep had always eaten some seaweed as part of their diet, but now they had to live entirely on seaweed- somehow their digestive system evolved to do this and they survived. This also meant that their systems evolved to extract the copper in seaweed so that if they only grazed on grass they would be poisoned. To this day, the islanders continue to maintain the 13 mile drystone "Sheepdyke" and every summer they host a sheep festival where the main activity is to rebuild the walls (and everyone is invited!)

The North Ronaldsay sheep are very special not just because they eat seaweed. The breed is also very old, from the Viking age, but unique from evolving on an isolated island. Their ancestry is traced from the Caspian Sea to Scandanavia to the Orkney Islands, making them descendants of the oldest sheep on the planet. The UK-based Rare Breed Survival Trust (RBST) lists North Ronaldsay sheep as a "Priority" meaning they are critically endangered with only 600 breeding pairs (more at risk than the Soay and Boreray!)

Sometimes, you're just in the right place at the right time. On my visit to North Ronaldsay, I was standing on the rocky shore when I heard a rumbling. Somehow I had the presence of mind to turn on my video camera and capture this amazing parade of North Ronaldsay sheep. When it was over, I could breathe again- it was nothing short of a thrill! Sound on! You don't want to miss the sound of hooves on the loose stones and what the little one said at the very end of the line.

Like the Soay on St. Kilda, the North Ronaldsay sheep are also a primitive sheep breed - which makes them hardy. It also means that there is a lot of variability of the color and qualities of the fleece between of the sheep in the flock and on different parts of the same animal. Why? Because nature favors diversity. Did you know carrots were originally white, yellow and purple and the Dutch bred carrots to be orange? Selective breeding often goes in the direction of taking plants and animals to be more alike than different. So, the primitive North Ronaldsay sheep are just as nature intended before domestication and farming.

North Ronaldsay sheep are double-coated, with tough guard hairs on the outside (for weather protection) and soft downy wool on the undercoat (for warmth). For readers interested in North Ronaldsay fleece and spinning, here's a wonderful video from Theresa George, a shepherd/spinner of North Ronaldsay sheep, who also has an article in Ply Magazine's Double Coated issue.

a tour of the North Ronaldsay Wool Mill

In 1996, the Island's Community Council established a Mini-mill in the former engine room of the North Ronaldsay lighthouse, to process the wool of the North Ronaldsay sheep. Now run by Ms. Jane Donnelly, the mill creates wool products from the island's sheep. Mills are generally set up to process fleece and wool within certain parameters (micron count, staple length, etc.) and it is difficult to find mills to process double coated fleeces. Mills also have wool minimums, making it doubly hard to find mills to process the wool of the smaller primitive breeds that are also small in number due to being endangered. So the mill at North Ronaldsay processes not only the North Ronaldsay sheep's wool, but also processes batches of Soay and Boreray wool from the Orkneys and the U.K.!

The mini-mill machinery was imported in 2003 from Prince Edward Island in Canada (and just for those of you, curious like me, that is 2,500 miles across the Atlantic Ocean to North Ronaldsay.) The mill is set up to scour, dry, de-hair (the kemp and coarse hair that is the outer layer of the double-fleece must be separated from the wool), spin and ply. The Wild Fibers tour group crammed into the tiny space too see all the stages of wool processing including the running of the plying machine - amazing!

A few more photos of the incredibly beautiful North Ronaldsay

I highly recommend Debbie Zawinski's book, "In the Footsteps of Sheep," for your Scottish adventure reading. Zawinski walks through Scotland picking up tufts of wool from fences, shrubs, and the ground, and spins the wool on a stick (not even a spindle with a whorl) and then, knits a stripe with that sheep's wool (foraged at that locale) to create the ultimate Scottish sheep breed pair of socks! Along the way of walking and wild camping, she tells stories of the encounters with the locals, tourists, the sheep and the land. It's a great read for spinners, knitters, walkers, and adventurers.

Zawinski's pluck, spins, and travel stories include saving an injured tup (ram) who tangled with a wire fence, with Jimmy, the island mechanic and former lighthouse operator of North Ronaldsay. True stories are incredibly inspiring, but a warning, that reading this book may cause you to book a ticket to Scotland!

references

George (2021) North Ronaldsay: The seaweed-eating sheep, Ply: The Magazine for Handspinners Issue 32: Double Coated

North Ronaldsay Sheep Fellowship

North Ronaldsay Sheep Festival

Robson & Ekarius (2011) The Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook, Storey Publishing

Fournier & Fournier (1995) In Sheep's Clothing: A Handspinner's Guide to Wool, Interweave Press, Inc.

Coulthard (2020) A Short History of the World According to Sheep, Anima Publishing

Cooper (2023) The Lost Flock: Rare Wool, Wild Isles, and One Woman's Journey to Save Scotland's Original Sheep, Chelsea Green Publishing

Parkes (2019) Vanishing Fleece: Adventures in American Wool, Harry N. Abrams Publisher

Zawinski (2015) In the Footsteps of Sheep: Tales of a journey through Scotland walking, spinning and knitting socks, Schoolhouse Press

Wild Fibers Magazine and Tours with Linda Cortright

COMING UP IN TRAVELS IN SCOTLAND POST 7: harris tweed

Thank you for reading my blog post. Travels in Scotland is a 12 part blog series filled with photos and stories of a fiber artist's journey through a beautiful country, encountering a land with a deep textile history, stunning landscapes, and of course sheep!

You can read all of the Travels in Scotland blog posts on my website. I invite you to travel along with me, along the coast and through the mainland hills seeing, experiencing and learning about this place called Scotland. Turas math dhuibh! (Good journey to you!) Amy

Write a comment

Eileen Baker (Tuesday, 23 April 2024 08:21)

Thank you for a very interesting post. My mother in law brought me back a bag of North Ronaldsay roving (the same as in your photo)when her cruise ship visited the islands this past summer. It perked my interest and I did some research on the sheep. How lucky for you to actually visit the island!

Your blog and videos and links were excellent! Hope to someday tour the Orkney Islands.