Welcome to my series of blog posts Travels in Scotland. Whether you're planning a trip, reliving a memory, or relaxing into some armchair traveling...thank you for joining me! Here I will show you images & share stories of my one month travels through Scotland. I'll cover this beautiful country of mountains, rivers, glens, islands, history, and, of course, fiber and textiles.

the black isle

Up past the northern city of Inverness, lies a peninsula called the Black Isle. A haven for birds and dolphins, the Black Isle was so named for its dark fertile soil. This area is also home to flocks of sheep. This post will explore how an "indie dyer" (the term that applies to independent small business people that hand-dye their own line of yarns for knitters and crocheters on a smaller scale than commercial businesses) is building relationships with shepherds in her home area and utilizing the natural resources available to bring an amazing product to market. I also write in this post, about how many sheep there are in all of Scotland and what's happening with the wool - with some surprising discoveries.

black isle yarns

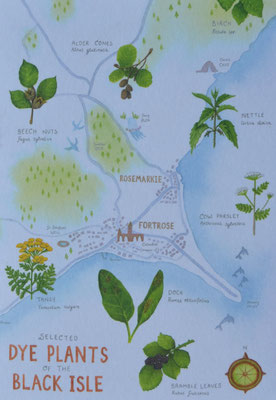

I was able to make an appointment and visit with Julie Rutter, owner of Black Isle Yarns to learn more about her yarn business. Julie had just returned from some "wild swimming" but spent more than an hour with me in her Studio-Shed chatting about her work and passion. Julie has established relationships with sheep farmers within a 50 mile radius of her home in Fortrose, Scotland on the Black Isle peninsula. Some of the farmers are commercial farmers that are raising sheep for meat. Some have smaller flocks, who are raising their sheep for meat but also may be spinners and knitters themselves and care about the quality of the animals’ wool coats. Some are raising a few sheep on smallholdings for the joy of it. Julie hand selects each fleece for Black Isle Yarns (Shetland, Cheviot, Bluefaced Leicester, Gotland) and then hand skirts all of the fleeces at her home before sending the wool to British mini-mills for processing into yarn. Once the yarn is spun according to Julie’s specifications (worsted or woolen; sock, aran or dk weight), the yarn is returned on cones ready to Julie to skein and begin the natural dyeing in her home studio. After collecting alder cones, beech nuts, nettle, tansy, and brambles, all foraged on the Black Isle, Julie dyes all her yarns naturally, without chemical dyes. Julie then takes her natural, unique, fully traceable all-British wool yarn to Scottish knitting shows and sells to customers directly and online. What makes Black Isle Yarns unique, is that the wool AND the natural dye material is all sourced by Julie on the Black Isle. This is a very local product and a very knowable provenance. Julie is one of a the indie dyers in Scotland producing a high quality, Scottish yarn. More about her unique story and business can be found in Issue 2 of Yarn: The Journal of Scottish Yarns. (And please see the end of this blog for a list of additional UK indie dyers/yarn producers.)

so many sheep, so little yarn

When visiting Scotland, one thing becomes quickly apparent: there is no shortage of hills, water and sheep. Sheep are grazing everywhere, literally (6.83 million sheep in Scotland). And to a fiber enthusiast like myself, it seems like paradise. I can’t help wanting to get my hands on some of that yummy, scrumptious, squeezable wool. So understanding why most of those cute sheep dotting the hillsides are farmed for meat instead of for their fleece, is a yarn mystery I’d really like to unravel.

Two quick stories from my visit to Scotland help to illuminate the complexities of why British wool is not universally being made into yarn. Story one: I stayed for two weeks on Glenorchy Farm in the center of Argyll and Bute, 15 miles south of Glencoe. This small family farm raises chickens, heritage breed Oxford pigs, horses, ponies, 4 Angus and 2 Scottish Highland steers, and a flock of 40 Swaledale sheep and 1 tup (ram) named Sid. Tristan and Fiona MacLennan spend 8,000 British Pounds per year on animal feed. They sell the meat locally and feed their family from the animals they raise. Tristan told me that their choice of sheep breed is first and foremost determined by the terrain of the glen (valley) in the Scottish Highlands. Questions like, will the sheep survive outdoors on their own when they’re put up on the hill? Can the sheep lamb on their own? Do the ewes make good mothers? Will the meat catch a good price in the market? These are the concerns of a farmer raising small flock in a rugged country. It may come as a surprise to some that Tristan and Fiona's Swaledale fleeces end up in their vegetable polytunnel for mulch and compost. The fact is...farmers receive very little compensation for wool fleeces. Farming is a business run on incredibly small margins. Thus, most farmers have a side business and for the MacLennans, it’s hospitality. But why isn’t their fleece worth more than compost?

Here is the second story: While out sightseeing on the West Coast of Scotland near Kilmartin Glen, we were walking up to the ruins of Carnasserie Castle and we had to pass through a narrow opening in the rock wall. At the same time, a truck with a trailer loaded with bales of sheep fleece was working its way down the hill (see photo below). The farmer’s wife had to open a gate to let the truck pass, so I took the opportunity to strike up a very quick conversation and asked her, “How many sheep’s fleeces were in the bales?” “Four hundred,” she said. “Are these going to the Wool Board?” And raising her hands to the heavens, “Yes and we won’t get anything for them!”

The British Wool Marketing Board (known as "The Wool Board") takes all the clipped fleeces from farmers across the UK, sorts and grades the wool, auctions the wool and pays the farmers at the end of the year based on prices achieved. According to The Wool Board, the wool is used for flooring, bedding, furnishings, insulation and apparel. With over 60 pure breeds in the UK and a variety of cross-breeds, the Wool Board experts train for five years before qualifying to sort and grade the wool. The Wool Board publishes yearly documents on the prices of each breed’s wool clip. In 2022, the Wool Board paid an average of 36.4 pence per kilo of wool. Even before you do think to do the conversions of US Dollars to British Pounds Sterling and kilos to pounds, you already know that this isn't much: converted to 45 cents for 2.2 pounds of wool, is a pittance to a farmer. It cannot even cover the cost of sheering and fuel for transporting the fleeces to the Wool Board.

So what happened to devalue British wool? We might say, “the vagaries of history.” Or the rise of microfibers and the fashion industry. Consumers change of taste for cotton and a closet full of easy-care garments away from a few sturdy, hand-washed wool stand-bys. Are fewer people knitting as time goes by?

Just like the rise of “Agri-business” that decimated small farms in the US, so has the rise of fast fashion and its preference for Merino, caused the decline of farming sheep for both meat AND their fine fleeces. However, just as the Farm to Table and CSA movements have grown out of the historical shift of small farms to enormous aggregrate farms, so too have the independent wool and yarn producers begun to bring back carefully crafted, independent and locally produced yarns. This is the sustainable, local, ecological business that Julie Rutter and Black Isle Yarns are a part of in the UK.

I queried the Wool Board through their email contact about how much knitting yarn is produced from the Wool Board’s clip, and they state, “25% of the clip that we grade at British Wool goes into knitwear. It is difficult to break this down.” So, we might assume that a good deal of that 25% is being commercially machine knitted and that independent yarn producers, like Black Isle Yarns, are picking fleeces before the farmers send them to the Wool Board.

I've discussed selective breeding in previous posts. If farmers cannot make money on sheep's wool, they will breed sheep for the best quality meat and disregard the qualities of the wool. This ultimately means that the genetics for fine quality wool of the various breeds of sheep, will diminish or be lost over time. How can this trend be reversed? The question of course remains, will knitters, crocheters and yarn enthusiasts first, and the general public second, spend, support and sustain these burgeoning businesses and the sheep farmers with whom they collaborate? Wool that has value...fleece turned into yarn...ultimately, people who will wear wool and use wool products...will we make the change?

scottish/UK indie yarn producers for you to investigate

· Black Isle Yarns Natural hand-dyed and locally sourced wool from the Black Isle Penisula, Scotland, spun in Britain

Marina Skua Hand-dyed yarn spun in the UK from local natural fibers both wool and alpaca in Somerset and the South-West of England

· Northern Yarn Shop British wool and yarn sourced from farms in Lancashire and Yorkshire

· Woolly Mammoth Fibre Co. Locally sourced and hand-dyed in Northern Ireland, UK

· The Wool Library Collective offering locally sourced Cheviot blended with soy or nettle

· Iona Wool 100% single origin Iona wool

· Uist Wool Natural undyed yarns and wool products from the Outer Hebrides

· North Ronaldsay Mini Mill wool products from the rare North Ronaldsay sheep

· Birlinn Yarn on the Outer Hebrides (Meg Rogers’ own flock)

· Shilasdair Yarns and The Isle of Skye Natural Dye Company British wool with a focus on natural dyeing

· Donna Smith, Shetland designer with her own wool yarn

· Alice Starmore, Hebridean knitting designer producing own yarn

· Kate Davies, KDD&Co, Shetland, Knitting designer, author and yarn producer

If you have any Scottish/UK independent yarn producers to add to this list, please use the comment section below - thank you!

Postscript

Julie Rutter set up a Black Isles Yarns shop in her side yard shed, and that is where I met her on a Friday afternoon in August 2023. I'd already been island hopping through the Hebrides and Northern Isles of Scotland with Linda Cortright and Wild Fibers Magazine Tours. So when Julie told me about other UK businesses similar to Black Isles Yarns and mentioned the mini-mill at North Ronaldsay, I shared about my recent visit to the Orkneys and showed her the thrilling video I made of the North end flock of North Ronaldsay sheep stampeding on the shoreline. That led Julie to tell me that she had recently traveled with her whole family this same summer to Loveland, Colorado (very near to my home of Boulder, Colorado) to celebrate her parents' 50th anniversary - and the thrill of their wild Bighorn Sheep sightings in the Rocky Mountains! Now that's a cultural exchange I can get excited about!

just some gratuitous pictures of sheep in scotland because we love them

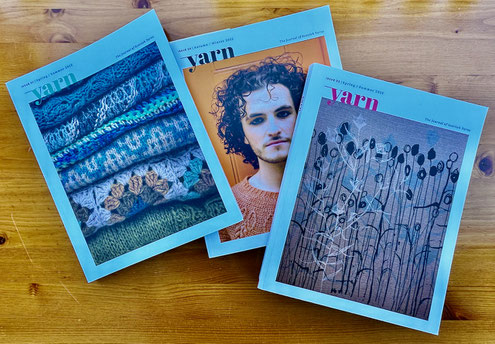

If you are interested in Scottish textiles - historical textile arts and what is currently happening in Scotland - then I recommend this new magazine begun in 2022. Yarn: The Journal of Scottish Yarns is a feast for the eyes and hands with stunning photography, which can be mail ordered or received in digital form. Every issue has colorful, in-depth stories followed by knitting AND crochet patterns produced by Scottish designers for The Journal of Scottish Yarns. This amazing journal is dedicated to uplifting wool, craft, producers, and sheep in Scotland and served as inspiration and research for my trip. Issue 5 is being released Spring/Summer 2024 and is available in digital form here and paper copies are being stocked soon in the UK and at select US online yarn stores (google to find one near you).

Another book recommendation for those interested in moving towards a sustainable clothing economy that includes sheep's wool....

Fibershed is an international movement with regional groups. Focusing on local is a key concept in reducing carbon and supporting producers in the area in which you live. Fibershed aims is to educate the public and the fashion industry about the circularity of agricultural systems and how people and industry can modify their practice to be part of the seed to soil regenerative process instead of relying on non-composting plastic products. Fibershed supports farmers and land stewards and is helping to revitalize the wool mill industry. Most importantly, Fibershed works with government towards effecting substantive change through policy and legislation.

You can learn more by reading founder Rebecca Burgess' book and here on their website. Fibershed also produces a podcast called "Weaving Voices." You can read the transcripts here or listen/find on Apple Podcasts and Spotify.

Why wool?

Wool is a naturally renewable resource. Just because it's been used for literally ages, doesn't mean it is old-fashioned.

Sheep are sheared for their fleece mostly once a year and then regrow that fleece. Fleece can be turned into insulation building products, felted into household products, or spun into yarn for knitted/crocheted clothing. Wool products are hard wearing and can last a lifetime. Wool breathes, is warm or cool even when wet, repels moisture, and stain-resistant: all properties that makes wool particularly good for clothing, suiting, homewares and especially outdoor activity wear.

When wool products have finished their usefulness, wool can be returned to the soil and easily biodegrades, unlike synthetics. Additionally, sheep are hardy and can be raised in many climates, making wool an ideal and sustainable product when used locally.

COMING UP IN TRAVELS IN SCOTLAND POST 11: Open studios in Argyll: Meeting a tapestry artist

Thank you for reading my blog post. Travels in Scotland is a 12 part blog series filled with photos and stories of a fiber artist's journey through a beautiful land, encountering a country with a deep textile history, stunning landscapes, and of course sheep!

You can read all of the Travels in Scotland blog posts on my website. I invite you to travel along with me, along the coast and through the mainland hills seeing, experiencing and learning about this place called Scotland. Turas math dhuibh! (Good journey to you!) Amy

Write a comment